The Goal of Aztec Religious Ritual & Prayer

The first thing that I feel the need to point out is the “goal” of Aztec rituals. The main goal is to honor the gods through nextlaoaliztli, “the giving of that which is right.” This term referred to the stereotypical blood sacrifice as well as many other things. This doesn’t mean that the goal of all Aztec religious rituals is to make a blood offering, all it means is that the primary goal of an Aztec religious ritual is to give the gods what they deserve – your reverence, honor, and the minor sacrifices of time, incense and so on given during any ritual. The rituals are designed to celebrate the gods, the bounty they have given us, and their presence in our life. It is to show our gratitude, and our love for the gods. I bring your attention to the idea of gratitude, because of the primary difference between the Aztec approach to the gods and many modern approaches: the idea that the gods deserve our gratitude and that we owe it to them, rather than the idea that the gods owe us and should be grateful for our attention.

While the idea that the gods should be grateful is mostly a modern Pagan concept, the idea that a god is there primarily to help us with the trivial issues of our life is present in Christianity as well. I am reminded of the time that a Christian told me that Catholics weren’t real Christians because their “Hail Mary’s” and such were repetitive prayers rather than real requests, and thus would not be answered. I asked her if the goal of her religion was getting her prayers answered, but she didn’t know how to respond. Similarly, many Neopagans tend to invoke deities to request that they perform favors for them. I cannot stress enough that this is not the goal of Aztec religious ritual. This is not to say that the Aztecs never made pleas to the gods for assistance – I think that is present in one form or another in most religions – but such prayers are not the main goal and you should never enter into a ritual simply with the intent to deliver a request to the gods. This brings us to the second point.

There are two main types of prayer in Aztec ritual. One is the “honor” prayer, that is, a prayer designed purely with the intent of praising the gods. They contain no petitions or pleas, but are mostly speeches or songs expressing the power, beauty, wisdom and awesomeness of various deities. The purpose of these prayers is pretty self-explanatory: reciting them honors the gods. Because of this, they are a typical part of many Aztec rituals. The second prayer is the “petition” prayer, that is the “please help me with X” prayer. Petition prayers may be individual or community petitions, and they may be very generalized or relatively specific.

To clarify what I said in the above section, petition prayers aren’t taboo or unacceptable, it is just that it’s important to go about them in the proper way. As said above, they should never be the main intent of your worship or the general bulk of your ritual. You should wait until you are well acquainted with the particular deity you wish to pray to before you petition them for assistance. Knowing a god beforehand is very important; and don’t get to know them with the intent to use them for prayer. Get to know deities out of a desire to worship, honor, and love them. Once you have done that, if you are in need, they tend to naturally look out for you, and you may actually find that you feel the need to make requests far less frequently than you once thought you did. The Aztec gods also have a tendency to issue requests to their devotees – you may find that following their requests, rather than the opposite, addresses the lacking areas of your life. If you don’t recieve outside guidance well and consistently refuse it, don’t expect help with your prayer requests. It would be like returning a gift to someone only to decide you want it back: pretty disrespectful.

So, when you eventually do find yourself in the position of wanting to request divine help, how do you go about it? That will be covered in the Ritual Guidelines section. For now, I just wanted to mention the basic idea.

Tlasojkamati Yehecatl Quipoloa . . .

Aztec woman in the household

The life of all Aztecs was the same everyday. At the early hours of the morning, they would get up and go straight to work. They would eat a light meal at midmorning usually made of maize gruel (atolli) at least the commoners. The nobles would eat light chocolate or something extravagent like that. Afterwards, they would return to work. Noble women would sometimes go and visit with other noble women. They would meet and talk about what was happening in society. Life was sometimes better for commoner women. They could go to the market and could hear about what happened in the empire. Noble women who had their every movements tightly controlled because of the political signifigance of their relationships, had to rely on servants for that information.

At noon, Aztec families would have their main meal and relax for a bit afterwards. They then would go back to work in the fields, or the house or the market. They would have a brief evening meal at the end of the day and go to bed at sunset.

Before in this site, I mention that a woman’s main job is to have children. This holds true as the most important job in the household. Having children is her number one job. If she bears sons, the fathers take over their education and then they go to school. If daughters, it is the womans job for the most part, to teach her how to spin, weave, cook and clean. These of course are the main jobs of can Aztec women in the house. She also may help the husband to work in the fields. She manages the slaves or servants if there are any, appointing them their jobs and chores. In a lower class home, it is her job to attend the market and buy their house needs. She can collect firewood and the usable water. She cooks and cleans. This was the role of most Aztec women. Very few held jobs outside the home, although there were other jobs for them.

An article written by Elizabeth Brumfiel shows that women adapted their weaving as the demand for tribute increased. As this was a job for homemakers, they changed the spindle sizes and shapes in order to make more cloth, but not taking away from the value and quality.

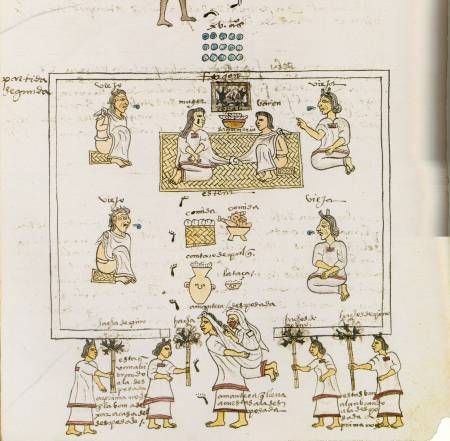

Aztec Marriage

Women were expected to marry and have children. This is what their lot in life was. If a woman didn’t marry, there were few reasons. One, her family must have needed her at home to help them with their other children or to make tribute cloth. It was also possible that she would join the priesthood and live in the church. She could also live as a prostitute but we will talk about that later.

Marriage was a step though that most women in Aztec society made. They had a strict marriage plan that was followed by all Aztec societies. The courtship was initiated by the boys family in most all cases. They would send a matrimonial agent to the house of the girl and make their plea. In Aztec culture, it was made that the first attempt be denied by the girls family, they usually claiming their daughter to be too young. But this was not to be taken seriously, it was simply their way of one wooing the other and it lasted for many days.

Once the offer was accepted by the parents of the girl, she was lectured most repetitively by her family about what she was to do as a new bride. She of course, was not allowed to offer an opinion and so listened respectfully as she was told she was no longer a child but a woman and to behave as so. It is unsure in Aztec society, even with Sahagun’s readings, if the girl was to give a dowry or if the boy offered gifts to her family. It is known that in Mayan society, a young man must work in the house of his in-laws for at least four years.

Once the wedding was announced, the relatives and friends of both families were invited to celebrate and the priests were ordered to pick the date for the wedding. They would pick a “good” day for the wedding to be held so that the new bride and groom would be prosperous. On the day of the wedding, the bride was washed, hair was cleaned, face was made up with ochre and powdered with sulfur purites, so to give the appearance of shining. Feathers of exotic birds were put on her arms and legs and she was dressed in the finest embroidered garments the family owned. At sunset, the groom’s family came to her house and would give their thanks and apologies to the family of the bride. Then the bride would kneel on a black cloth and an older woman would pick her up and carry her on her back to the house of the groom. The female relatives would follow in line behind. Once at the house of the groom, the bride would be set upon the hearth and the groom would sit next to her on her right. The matrimonial agent would tie the ends of the man’s shirt to the brides garment and then feed each of them four bites of maize cake. This signified the marriage ceremony and they were now husband and wife.

After this, priestesses would come and lead the new couple to a room where they were to be left alone, with only priestesses outside to stand guard. The rest of the family would have festivities for the next four days. Marriage signified the bondage of a woman transferring from their father to their husband.

The new couple were made to live in the calpulli of the husband. A woman that was worthy of marriage was to be a virgin and to always be faithful to their husbands. This was demanded of them and was punished by means of stoning. No laws like this applied to the males. They could have slept with prostitutes before marriage and could have more than one wife, although polygyny was mostly observed by the nobles.

Omácatl

In Aztec mythology, Omacatl (“two reeds”, “Ome”-“Acatl”) was a god of feasting, holidays and happiness, and an aspect of Tezcatlipoca. He is represented as a black-and-white figure, squatting and eating. As a god worshipped primarily by the wealthy, he wore a crown and a flower-decorated cloak, and carried a sceptre. At his festivals, maize effigies of Omacatl were eaten and (allegedly) the participants held orgies to honor him. A manifestation of Tezcatlipoca, presided over banquets and feastings.

Nanauatzin

In Aztec mythology, the god Nanahuatl (or Nanauatzin, the suffix -tzin implies respect or familiarity; Classical Nahuatl: Nanāhuātzin [nanaːˈwaːtsin]), the most humble of the gods, sacrificed himself in fire so that it would continue to shine on Earth as the sun, thus becoming the sun god. Nanahuatl means “full of sores.” In the Codex Borgia, Nanahuatl is represented as a man emerging from a fire. This was originally interpreted as an illustration of cannibalism.

The Aztecs had various myths about the creation, and Nanahuatl participates in several. In the legend of Quetzalcoatl, Nanauatl helps Quetzalcoatl to obtain the first grains which will be the food of humankind.

In Aztec mythology, the universe is not permanent or everlasting, but subject to death like any living creature. However, even as it dies, the universe is reborn again into a new age, or “Sun.” Nanauatl is best known from the “Legend of the Fifth Sun” as related by Sahagun.

In this legend, which is the basis for most Nanahuatl myths, there had been four creations. In each one, one god has taken on the task of serving as the sun: Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, Tlaloc, and Chalchiuhtlicue. Each age inevitably ended because the gods were not satisfied with the human beings that they had created. Finally, Quetzalcoatl retrieves the sacred bones of their ancestors, mixes them with corn and his own blood, and manages to make acceptable human beings. However, no other god wants the task of being the sun.

The gods decide that the fifth, and possibly last, sun must offer up his life as a sacrifice in fire. Two gods are chosen: Tecciztecatl and Nanauatl. The former is chosen to serve as the sun because he is wealthy and strong, while the latter will serve as the moon because he is poor and ill. Tecciztecatl, who is proud, sees his impending sacrifice and transformation as an opportunity to gain immortality. The humble Nanauatl accepts because he sees it as his duty.

During the days before the sacrifice, both gods undergo purification. Tecciztecatl makes offerings of rich gifts and coral. Nanauatl offers his blood and performs acts of penance.

The gods prepare a large bonfire that burns for four days, and construct a platform high above it from which the two chosen gods must leap into the flames. On the appointed day, Tecciztecatl and Nanauatl seat themselves upon the platform, awaiting the moment of sacrifice. The gods call upon Tecciztecatl to immolate himself first. After four attempts to throw himself onto the pyre, which is giving off extremely strong heat by this time, his courage fails him and he desists. Disgusted at Tecciztecatl’s cowardice, the gods call upon Nanauatl, who rises from his seat and steps calmly to the edge of the platform. Closing his eyes, he leaps from the edge, landing in the very center of the fire. His pride wounded upon seeing that Nanauatl had the courage that he lacked, Tecciztecatl jumps upon the burning pyre after him.

Nothing happens at first, but eventually two suns appear in the sky. One of the gods, angry over Tecciztecatl’s lack of courage, takes a rabbit and throws it in Tecciztecatl’s face, causing him to lose his brilliance. Tecciztecatl thus becomes the moon, which bears the impression of a rabbit to this very day.

Yet the sun remains unmoving in the sky, parching and burning all the ground beneath. Finally the gods realize that they, too, must allow themselves to be sacrificed so that human beings may live. They present themselves to the god Ehecatl, who offers them up one by one. Then, with the powerful wind that arises as a result of their sacrifice, Ehecatl makes the sun move through the sky, nourishing the earth rather than scorching it.

The fifth sun is identified with Tonatiuh.

Matlalcueitl

Matlalcueitl (also Matlalcueyetl or Matlalcueje or “Matlecueye”) (She of the Green/Blue Skirt)(perhaps translating as “jade-skirted”) is a goddess of life-giving rain and of song in Tlaxcalan mythology. They gave her name to a now dormant volcano Matlalcueitl. The Tlaxcaltecah were a separate group of Nahuatl speakers that were subjugated to the Aztecs at the time of the Spanish colonization of the Americas. In Aztec Mythology, Matlalcueitl was identified with Chalchiuhtlicue and with her consort, the ancient rain god Tlaloc.

Matlalcueitl, or Matlalcueye, was the second wife of Tláloc, the Aztec god of rain, after Tezcatlipoca had abducted his first wife Xochiquetzal. She was the goddess of rain, Matlalcueye, and, in honour, this name was given to an extinct volcano located between Puebla and Tlaxcala, to the east of the Basin of Mexico; the same volcano was renamed La Malinche during the Spanish colonial period.

Ilamatecuhtli

Ilamatecuhtli, an ancient central Mesoamerican earth and sky goddess, was associated with the earth and with the corn (maize) crop as the goddess of the old, dried-up corn ear. She was honoured at the feast Títitl (“shrunken”, “withered”, or ” wrinkled”). She was also the last the 13 Lords Of The Day.

Huehuetéotl

Huehueteotl (“Old god”; aged god in Nahuatl) is a Mesoamerican deity figuring in the pantheons of pre-Columbian cultures, particularly in Aztec mythology and others of the Central Mexico region. He is also sometimes called Ueueteotl. Although known mostly in the cultures of that region, images and iconography depicting Huehueteotl have been found at other archaeological sites across Mesoamerica, such as in the Gulf region, western Mexico, Protoclassic-era sites in the Guatemalan highlands such as Kaminaljuyú and Late-Postclassic sites on the northern Yucatán Peninsula.

Huehueteotl is frequently considered to overlap with, or be another aspect of, a central Mexican/Aztec deity associated with fire, Xiuhtecuhtli. In particular, the Florentine Codex identifies Huehueteotl as an alternative epithet for Xiutecuhtli, and consequently that deity is sometimes referred to as Xiutecuhtli-Huehueteotl.

However, Huehueteotl is characteristically depicted as an aged or even decrepit being, whereas Xiutecuhtli’s appearance is much more youthful and vigorous, and he has a marked association with rulership and (youthful) warriors.

An Aztec religious observance was celebrated via boys hunting small animals such as snakes, lizards, frogs and even dragonflies larvae in the swamps to give them to the elders who served as the guardians of the fire deity. As a reward for these offerings, the priest would give them food. At these occasions the god was demonstrated as young with turquoise and quetzalfeathers for ceremonial purposes. Later during the month he appeared as ageing and tired, covered with the colours of glow; gold, black and red. Perhaps this has led to the confusion of the deity being two separate ones, as being displayed as such, or vice versa.

Another, more dramatic one, was a celebration consisting of feasts and a time of ceasing hostilities. The Aztecs cut out the hearts of human sacrifices, followed by burning them on coal. As a result of this, the people would regain Huehueteotl’s favor through the gods elements – fire and blood.

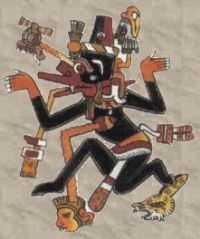

Éhecatl

Ehecatl (Spanish: Ehécatl, Nahuatl: ehēcatl; Classical Nahuatl: Ecatl [ˈekatɬ]) is a pre-Columbian deity associated with the wind, who features in Aztec mythology and the mythologies of other cultures from the central Mexico region of Mesoamerica. He is most usually interpreted as the aspect of the Feathered Serpent deity (Quetzalcoatl in Aztec and other Nahua cultures) as a god of wind, and is therefore also known as Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl. Ehecatl also figures prominently as one of the creator gods and culture heroes in the mythical creation accounts documented for pre-Columbian central Mexican cultures.

Since the wind blows in all directions, Ehecatl was associated with all the cardinal directions. His temple was built as a cylinder in order to reduce the air resistance, and was sometimes portrayed with two protruding masks through which the wind blew.

As the fourth sun was destroyed in the Aztec creation myth (due to the gods not being satisfied with the men they had created) the gods gathered in Teotihuacan. There Nanahuatzin and Tecciztecatl jumped into a sacrificial fire and became the sun and the moon. They remained immobile until Ehecatl blew hard on them. At first only the sun moved, but once the sun started moving the moon moved also.

Xiuhcoatl

In Aztec religion, Xiuhcoatl was a mythological serpent, it was regarded as the spirit form of Xiuhtecuhtli, the Aztec fire deity, and was also an atlatl wielded by Huitzilopochtli. Xiuhcoatl is a Classical Nahuatl word that literally translates as “turquoise serpent”; it also carries the symbolic and descriptive meaning, “fire serpent”.

Xiuhcoatl was a common subject of Aztec art, including illustrations in Aztec codices and its use as a back ornament on representations of both Xiuhtecuhtli and Huitzilopochtli. Xiuhcoatl is interpreted as the embodiment of the dry season and was the weapon of the sun. The royal diadem (or xiuhuitzolli, “pointed turquoise thing”) of the Aztec emperors apparently represented the tail of the Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent.

The Xiuhcoatl was typically depicted with a sharply back-turned snout and a segmented body. Its tail resembled the trapeze-and-ray year sign, and probably does represent that symbol. In Nahuatl, the word xihuitl means “year”, “turquoise” and grass”. The tail of Xiuhcoatl is often marked with the Aztec symbol for “grass”. The body of the Xiuhcoatl was wrapped with knotted strips of paper, linking the serpent to bloodletting and sacrifice.

In the Postclassic period, the Xiuhcoatl fire serpent was associated with the three concepts associated with its tail-sign; turquoise, grass and the solar year. All three of these concepts were associated with fire in central Mexico during the Postclassic, with dry grass and the solar year being closely identified with fire and solar heat. Page 46 of the pre-Columbian Codex Borgia depicts four smoking Xiuhcoatl serpents arranged around a burning turquoise mirror. A turquoise-rimmed mirror has been found at the Maya city of Chichen Itza, with four fire serpents circling the rim. The archaeological site of Tula has warrior columns on Mound B that bear mirrors on their backs, also surrounded by four Xiuhcoatl fire serpents.

Although the Fire Serpent can be easily traced back to the Early Postclassic period in Tula, its ultimate origins are unclear. During the Classic Period, the War Serpent of Teotihuacan was probably a forerunner of Xiuhcoatl, it was also depicted with the grass symbol, flames and the trapeze-and-ray year symbol.

Xiuhcoatl was considered to be the nahual, or spirit form, of the Aztec fire god Xiuhtecuhtli. It was a lightning-like weapon borne by Huitzilopochtli. With it, soon after his birth he pierced his sister Coyolxauhqui, destroying her, and also defeated the Centzon Huitznahua. This incident is illustrated on a fragment of broken sculpture excavated from the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan. The fragment was originally a part of a large stone disk that depicted the fallen Coyolxauhqui with the Xiuhcoatl fire serpent penetrating her chest. This Xiuhcoatl wielded by Huitzilopochtli symbolises the forces of darkness being driven out by the fiery rays of the sun.

Tonatiuh, the Sun god, was guided across the sky by Xiuhcoatl, and was used by him as a weapon against his underworld enemies, the stars and the moon.

During the Panquetzaliztli ceremony, Xiuhcoatl was represented by a paper serpent with red feathers emerging from its open maw to represent flames. During the ceremony, burning torches also symbolised Xiuhcoatl and a serpent dance was performed.